A sea of stone - biodiversity and history

Bella S. Galil

National Institute of Oceanography

POB 8030, Haifa 31080,

Israel

|

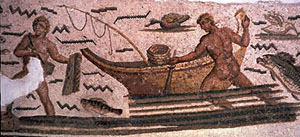

Note fishing methods (rod and line, trap,

drag net, sling net) and fish so ably depicted as to allow

scientific identification.

Ancient mosaics of fish and fishing methods in the Mediterranean Sea

illustrate Aristotle, Pliny and Oppian.

|

"Infinite and beyond ken are the tribes that

move and swim in the depths of the sea, and none could name them

certainly; for no man hath reached the limit of the sea, but unto three

hundred fathoms less or more men know and have explored the deep". |

With these words, Oppian gives us the ancient world view of the sea.

A native of Cilicia, present-day Gulf of Iskendrun, Oppian lived during

the latter half of the second century CE and is the author of

Halieutica, a five-volume poem on fish and fishing. In 3,500 lines of

verse he classifies and characterizes the fish, fishing seasons, and

ancient fishing methods in the waters of the Mediterranean Sea.

|

Head of Oceanus crowned with lobster legs and surrounded by

torpedo, rockfish, moray eel, squid, sea urchin, crab, octopus and

panaeid shrimp.

Oppian was not the first to describe the Mediterranean and its fish.

The earliest surviving record of the region's marine life appears in a

5th century BCE collection of essays entitled Corpus Hippocraticum.

The anonymous author classifies edible fish according to the quality of

their flesh and their habitat: rock fish, migratory fish, fish living on

the seabed, predators, and plant eaters. In the 4th century BCE, the

Greek philosopher Aristotle laid the foundations of zoology in his

ten-volume work on animal life, Historia animalium. Scholars of

marine life relied on his work for the next two millennia. Pliny the

Elder, devoted a volume of his Historiae Naturalis to sea

|

A fisherman sits on a rock by the seaside.

creatures, naming 74 species of fish. Romans considered marine fish

superior to freshwater fish and prices reflected their preference: Pliny

the Elder grumbled about the extravagance of his generation, and

complained that a high quality fish might cost as much as three cooks.

Not surprisingly, the fish preferred in antiquity are today's favorites

too: sea bass, grouper, striped sea bream, mullet and meager, as well as

oysters, squid, shrimp, and sea urchins.

In the 1st century BCE oysters and fish were raised commercially

around the Bay of Naples: six thousand moray eels were dispatched for a

victory feast of Julius Caesar. Affluent Romans boasted ponds stocked

with rare imported fish, which they treated as pets. Emperor Claudius'

mother is said to have hung gold rings in the nostrils of her favorite

moray eel. Mosaic floors from Africa Proconsularis (present day Algeria,

Tunisia and Libya) depict ponds teeming with fish - probably a

provincial effort to emulate the fashions of Rome. One marine mosaic

discovered in Achola in Tunisia is so accurate as to allow scientific

identification of the fish.

|

Fisherman mending a net.

Mosaic floors in the ruins of splendid villas portray the fishing

methods of the ancient world as if they were illustrations commissioned

for Oppians' four methods of fishing: rod and line, harpoon, trap and

net. In one mosaic, a fisherman sits on a rock by the seaside, wearing a

broad-brimmed straw hat and a short cloak to protect himself from the

burning sun or the morning chill; a basket of bait hangs from his waist.

He casts his line into the sea, crosses his legs, and tries his luck

with the philosophical patience that has characterized fishermen

throughout the ages. Another mosaic shows a fisherman, his muscles

bulging from the effort of pushing his barque through the surf. In the

shallows beside the boat is another fisherman about to cast his sling

net, a circular net with weights fastened around its edge. The fisherman

has folded the net onto his right arm, ready for action, and he lies in

wait for the fish passing by in the shallow water. When a shoal

approaches, he casts his net and the weights spread it to its full

extent; as it lands on the seabed, it traps the fish beneath.

|

A fisherman pushes his barque through the

surf. In the shallow another fisherman is about to cast his sling

net.

In another section of the same mosaic, a fisherman impales an octopus

hidden under a rock with a trident, and since the octopus may put a

valiant fight, the fisherman has a large club with which to stun his

catch. Pliny and Oppian both relate how fishermen locate the hiding

place of an octopus by the empty shells strewn roundabout. Two fishermen

sit in a small boat depicted in another mosaic. One plies the oars while

the other pulls on wickerwork traps. Traps like these were used to catch

lobsters and octopuses; they were placed in the sea in the evening and

raised at dawn - a fisherman in another boat shows off his prize - a

large lobster.

These ancient mosaics of marine life do not pretend to show the

natural habitat of the fish. Neither were they produced solely as works

of art. Due to their reproductive capacity, fish were considered sacred

fertility symbols by the people residing along the shores of the

Mediterranean. The various illustrations of sea creatures at the moment

they are raised on a hook or trapped in a net, are a celebration of the

abundance and fecundity of the sea.

|